Virtues, Jordan Peterson, and Thomas Aquinas

What Peterson's rules and the virtue tradition have to say to each other

Dr. Jordan Peterson.

Image credit: Shane Bart Balkowitsch, Nostalgic Glass Wet Plate Studio, Bismarck, North Dakota, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

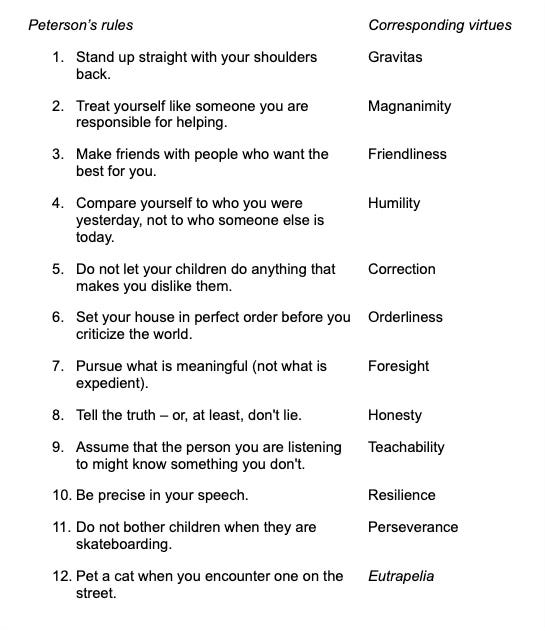

I’ve been re-reading Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos to confirm an insight I haven’t seen anywhere else: the rules map convincingly to the classical idea of the virtues. 12 Rules, which was published in 2018 and has sold many millions of copies, presents a masterful integration of research and insight from psychology, philosophy, and personal experience, condensed into 12 rules for how to live well. Each of these 12 rules corresponds to one of the classical virtues.

Regular readers will know that by “virtue” I do not mean a vague label for any positive abstract noun, like tolerance, or enthusiasm, or innovation. I am referring to a very specific set of good habits that have been identified and isolated over the centuries, and more recently subjected to extensive empirical testing.1

Combining the Rules with the virtue tradition isn’t a perfect one-to-one mapping, but it’s close enough that each can contribute something important to the other: Peterson’s rules enrich our understanding of several virtues, and the virtue tradition shows how to make living by those rules easier.

Deepening our understanding of the virtues

Mapping the rules to the virtue tradition means that the rules aren’t only an “antidote to chaos,” as important as that is: they also contribute to and become part of the most enduring guidance to happiness and human flourishing in human history.

It’s difficult to say something new about a 3,000 year old idea like virtue, but 12 Rules does that. For example, recognizing that Rule 8, “Tell the truth – or, at least, don't lie,” is about the virtue of honesty tells us some very important things about that virtue. Peterson lays out the harms that arise from even small lies. Many of us think of ourselves as basically honest even though we tell the occasional — or not so occasional — little untruth because it’s more convenient, or because we don’t want to hurt someone’s feelings. Peterson notes that “Taking the easy way out or telling the truth — these are not merely two different choices. They are different pathways through life. They are utterly different ways of existing.”2

He shows that when we tell little lies for the sake of convenience, we distance ourselves from reality and we become, steadily, more inauthentic. We begin to blind ourselves to who we really are, because “If you will not reveal yourself to others, you cannot reveal yourself to yourself.”3 As a result, “so much of what you could be will never be forced by necessity to come forward.”4 He then draws from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Viktor Frankl to argue the case that such petty lies can lead, ultimately, to totalitarianism, because “Untruth corrupts the soul and the state alike, and one form of corruption feeds the other.”5

Making it easier to live by Peterson’s rules

One of the most frequent complaints you read about the 12 Rules among online fans is the difficulty of remembering all the rich advice in the book in order to put it into practice. But we know a lot about how to cultivate the habits of human excellence that we call the virtues, and we can use this knowledge to help anyone who wants to adopt Peterson’s Rules. The behaviors encouraged by each rule are parts of a habit, and can be cultivated, like any habit, through daily practice that becomes easier and ultimately almost automatic. One is not doomed to have to memorize all the rules and keep checking against them: through daily practice, they become part of who we are.

For example, recognizing that Rule 8 is embodied in the virtue of honesty makes it easier to live by this rule. Instead of being overwhelmed when we read about all the grave dangers of telling small untruths, we can begin to cultivate the virtue — the habit — of honesty. We do this in the same way we would cultivate any other habit, through small, daily practice (thus following Peterson’s advice to “start small” when making a change in your life6). We will come to realize that through such practice, living the rule by living the virtue of honesty gets steadily easier, until it becomes so much a part of us that we will readily speak the truth without hardly any effort or question. A person who has cultivated the virtue — the habit — of honesty no longer has to keep reminding himself of Rule 8.

Anyone can try this. Each day, pay particular attention to your speech, and whenever you catch yourself bending the truth even slightly, pause and try to rephrase more accurately, or else, if it’s too late and the moment has passed, reflect on how you might phrase what you said differently next time. It will get easier each day.

The virtues

The virtues are specific habits of excellence, like honesty, courage, justice, and wisdom, that were honored in every major civilization from the ancient Greeks on forward, and in every major religion.7 They are universal, in the sense that all cultures value honesty above falsehood, courage above cowardice, or wisdom above stupidity. They are habits, so that the more one practices them, the easier and more natural they become. Someone who has practiced the virtue of honesty finds it very easy to be honest: it becomes a habit. And, pretty much anyone can acquire any of the virtues, through regular practice. So if someone is a chronic liar, that does not mean (except perhaps in very rare cases) that he or she has a genetic defect. It just means that they have not yet acquired the virtue of honesty. And they can, through regular practice.

Indeed the virtues are so universal, so generally agreed upon across times, places, and cultures, that many believe they are part of our human nature, a sort of “human operating system.” They are like mental muscles, so that when we try to develop a particular virtue, we’re not adding something new or foreign to ourselves, but just exercising an already existing muscle—developing a capacity that we already have. Contemporary empirical research shows that as we grow in any of the virtues, we become both happier and healthier. This makes sense if the virtues are innate human capacities, because growing in them means fulfilling those capacities and contributing to our flourishing.

Categorizing the virtues

There are many and various attempts at categorizations of the virtues. By far the most complete and internally consistent is that of medieval philosopher Thomas Aquinas. Many people, especially those who follow the Stoic philosophers, are familiar with the four “cardinal” virtues of practical wisdom, justice, courage, and self-discipline.8 Few, though, can say why these four hold a central place. Aquinas explains that these four collectively address our cognitive, behavioral, and affective domains: our thoughts (practical wisdom), our actions (justice), and our feelings of repulsion, or fear (courage), and feelings of attraction, or desire (self-discipline).

Practical wisdom is the habit of making wise decisions and leads to excellence in thinking, at least about practical subjects, because most of our thoughts throughout the day are ordered toward some decision or another. (Abstract thinking has its own, separate set of virtues).

Justice is the habit of treating others fairly and with respect for their dignity, and leads to excellence in our action, because most of our actions throughout the day are typically interactions with others.

Courage and Self-discipline both help us deal with our feelings, one each for our feelings of attraction and repulsion: our desires and our fears. Self-discipline is the habit of only following our feelings when it makes sense to do so, and Courage is the habit of moving ahead despite fear.

Each of these cardinal virtues has several “partial” virtues associated with it.9 They are called “partial” because each covers some subset of our functioning within or related to the cardinal virtue, but each of the partial virtues is also a virtue in itself. (And the cardinal virtues are called “cardinal” from the Latin cardo, which means pivot—the partial virtues all pivot around the cardinal virtues.)

The partial virtues and how the are associated with each of the cardinal virtues, according to St. Thomas Aquinas.

12 of these partial virtues align with Peterson’s 12 rules. Here they are, organized by their cardinal virtues.

Self-discipline

Self-discipline is the habit for dealing with desires, and so its partial virtues address different types of desires. Gravitas is the virtue for bringing excellence to our desires to move, so that instead of fidgeting or slouching, we stand and move gracefully. Orderliness is the virtue for our desire to get things done, and Eutrapelia, or Good Leisure, is the virtue for our desire to rest. Restraint is the virtue for dealing with desires to do petty or trivial things — such as [examples], and Humility is the virtue for dealing with desires to do great things, such as feeding the hungry or saving the planet.

Rule 1: “Stand up straight with your shoulders back,” corresponds to the virtue of Gravitas. This is the rule and the habit of maintaining a posture that will encourage respect from others. Peterson writes: “Walk tall and gaze forthrightly ahead,” so that people, “including yourself, will start to assume that you are competent and able (or at least they not not immediately conclude the reverse.) Emboldened by the positive responses you are now receiving, you will begin to be less anxious.”10

The virtue of Orderliness is the habit of doing things in some predetermined order, towards a particular purpose. Rule 6: “Set your house in perfect order before you criticize the world” provides an original insight into the virtue of Orderliness. In it Peterson observes that some people have a strongly negative, even hostile, attitude to their own lives, to other people, and even to all of humanity. (In the book, he gives the sad example of high school mass murderers). Peterson argues that the root cause of this hostility is their dissatisfaction with the chaos in their own lives. Living Rule 6, the virtue of Orderliness, corrects for this.

Eutrapelia is the habit of regularly taking time for refreshing relaxation. Rule 12: “Pet a cat when you encounter one in the street,” tells us to seize the opportunities for joy in life, as a remedy to the sometimes inexplicable and overwhelming suffering that life can bring.

Rule 4, “Compare yourself to who you were yesterday, not to who someone else is today,” helps us realize the virtue of Humility, the habit of having an accurate assessment of ourselves and our abilities.

Courage

Courage is the habit of moving forward despite being afraid of the challenge ahead of you. Its partial virtues include resilience and perseverance, for dealing with (respectively) mental and physical challenges that may be insurmountable but still have to be endured, and magnanimity, for dealing with challenges that can be overcome.

Rule 10, “Be precise in your speech,” contains an important insight into the virtue of resilience. Resilience is the virtue — the habit — of enduring mental challenges, like anxiety or depression. Peterson argues that we have a tendency to obscure the challenges we face in life by being imprecise in how we think and talk about them. He gives the example of failing marriages, where neither spouse is willing to bring up the small (or large) irritations and concerns that are harming the relationship, for fear that “a monster lurks underneath all disagreements and errors.” The “monster” could be the thought that my marriage is doomed no matter what, and/or that it’s all my fault; either way, I’d rather not talk about it. When we are precise in naming our fears, when we reframe them as challenges, that’s the first step in cultivating the habit of enduring them, the virtue of resilience.

Perseverance is the habit of enduring physical challenges and suffering, for a good reason — or because we have no alternative right now. Rule 11, “Do not bother children while they are skateboarding,” embodies this. What Peterson means by this rule is when children are doing something physically challenging, like skateboarding tricks, you should leave them alone, because they are deliberately testing their abilities and limits, and helping themselves grow. When you practice enduring a physical challenge, that strengthens the virtue of perseverance — the perseverance muscle — and you can use that virtue in any other circumstance that calls for physical endurance.

Magnanimity is the habit of taking on big challenges with enthusiasm. It corresponds to Peterson’s Rule 2, “Treat yourself like someone you are responsible for helping.” The biggest challenge we face in life is that of our own personal growth—making the best we can out of the one life we have.

Justice

Justice is the habit of treating others fairly by giving them what is due to them. It has several partial virtues, including honesty, friendliness, and correction. Each is the habit of giving what is due in a particular domain. Honesty, in communication, where we owe others the truth; Correction, where others under our authority do something wrong, where we owe them, as a matter of justice, feedback and, if necessary, punishment; and Friendliness, in interactions with others, where we owe them pleasant behavior.

Rule 8, “Tell the truth – or, at least, don't lie,” embodies the virtue of Honesty. Rule 5, “Do not let your children do anything that makes you dislike them,” is an important instance of the habit of Correction. Rule 3, “Make friends with people who want the best for you,” represents, and provides an original insight into the virtue of friendliness. The rule warns us against false friendships, where we are trying to help another just so that we feel good about ourselves, or where we’re enabling self-destructive behavior.

Practical Wisdom

Practical wisdom is the habit of making wise decisions, and includes partial virtues for gathering relevant information as well as for ensuring that a decision will be implemented well .

The virtue of Teachability, the habit of learning well from others, is an example of the former, and is embodied in Rule 9, “Assume that the person you are listening to might know something you don’t.”11

The virtue of Foresight is the habit of setting and following goals and is an example of the latter; in order for a decision to be implemented well it should be consistent with one’s goals. Rule 7 is “Pursue what is meaningful (not what is expedient).” Peterson describes the difference between the two: “What is expedient works only for the moment. It’s immediate, impulsive, and limited. What is meaningful, by contrast, is the organization of what would otherwise merely be expedient into a symphony of Being… Meaning is when everything there is comes together in an ecstatic dance of single purpose.”12 I cannot think of a more compelling and poetic way of describing the importance of organizing one’s life towards a purpose via a set of goals, and that’s the virtue of Foresight.

The takeway: Peterson’s rules give us new insight into each of twelve virtues, and if you’d like to strengthen your ability to live any one of those rules, practice growing in the corresponding virtue.

For a summary of how I got here, see https://superhabit.substack.com/p/superhabits.

p. 209

p. 212

Ibid.

p. 215

p. 157

Virtues like justice, humility, truthfulness, resilience or patience, and gratitude are found in Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Confucianism, and Shinto, among others.

Their more traditional English names are prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance, but some of those names have shifted in meaning.

[describe the different types of parts]

12 Rules for Life, p. 28.

The Latin word for this virtue is docilitas, often translated as “docility,” but docility, like so many in the virtue vocabulary, has suffered from serious semantic drift, so that it is now more typically taken to mean submissiveness, and that is not at all what we mean here. Teachability is the habit of paying attention to others, especially those with greater experience, so that we can learn from them.

Ibid., p. 201.