In July I delivered keynote speeches at the first ever Cardinal Newman Society Leaders Conference in Houston and at the 14th annual Napa Institute Conference in Napa, CA. Here is a lightly edited version of the text, with the key slides and video clips.

A year ago we were blessed with our first grandchild, Owen, so recently we’ve had the pleasure of watching him learn to walk. Here is Owen, taking his first steps — let’s watch him in slow motion.

Notice how he, like any child learning to walk, has to concentrate, really hard, tongue between his teeth, on every step. Why? Because he has not yet developed the habit of walking. Soon enough though, we know that he will develop that habit, and won’t give a second thought to the effort of walking.

Wouldn’t it be great if children could learn every habit that is important to success in life, in the same way that they learn to walk? But they don’t. There are habits of thought, action, and feeling, which are vitally important for making decisions, relating to others, and managing emotions, that have to be taught. As they were taught, from childhood, in many of the greatest civilizations in history, and even in our own civilization, until recently.

But for the vast majority of our children, these habits are no longer being taught, and haven’t been for some years now. As a result, in the same way that Owen, before he had the habit of walking, had to really concentrate on every step, we see too many people struggling with things like making decisions, relating to others, and managing their emotions.

Why does this matter? So some people have to work a little harder on making decisions, on their relationships, on managing their feelings. Does this matter? Here’s why it matters. It’s because these missing habits are a major root cause of most of the problems plaguing our society today.

Think about it: poor decisions in the personal lives in our children, and, as they grow up, in businesses and in government, are having all kinds of catastrophic consequences. The inability to establish and maintain human relationships is at the root of everything from the declining marriage rate, and all the terrible consequences that flow from that, to the vast divisions in our country, where neighbor hates neighbor, just because of who you vote for. And the very real pandemic of anxiety and depression among our young people is the result, in significant part, of an inability to manage emotions.

It’s all because these habits of thought, action, and feeling are missing; they haven’t been taught.

Have you noticed how young people — your younger employees, or your students, for example — seem to be so fragile. Every time they have a difficult decision to be made, or they have a challenging interaction with others, or someone is overwhelmed by a strong emotion, they have to work really hard at dealing with it. It’s like a new crisis every time, instead of being in the habit of handling it.

Just like taking every step was so difficult for little Owen, before he had the habit of walking, every major decision, relationship question, or big emotion is exhausting, because they do not have the habits for dealing with such experiences.

Even making a phone call can be a cause of anxiety. One young person reported having a favorite “pump up song” that she plays to get herself energized before she has to make a phone call. There’s even a woman called “the phone lady,” who teaches phone etiquette, to help people get over “telephonophobia” — for $195 an hour.1

This basic set of habits of thought, action, and feeling have largely gone missing from our society. But not totally. Interestingly enough, these habits are being rediscovered in a variety of places, places where human effectiveness is taken very seriously, such as the Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania, where they call these habits “character strengths;” the Center for Positive Organizations at the University of Michigan, where they call them “positive traits;” in research by management consulting firms like Deloitte, where they call them “capabilities;”and McKinsey, where they are “distinct elements of talent;” and in some (very few) universities, like my own, the Catholic University of America’s Busch School of Business, where we call them by their real name.

What are they called, these habits of thought, action, and feeling? Some of you can see where I’m going with this (… because it’s in the title of my talk.) These habits are the virtues.

And this is usually where it goes wrong.

Because most people, when they hear “virtue,” they think “be a good person. ” It’s as if I’m coming to the Napa Institute to tell you all to be good people. And what’s your natural reaction to that? It’ll be like Charlie Brown sitting in class, with his teacher talking. All you hear is “Wah wah wah - virtue - wah wah wah.”

You’ll tune me out. It’s not that anyone here is against being a good person. Anyone here against being a good person?

I didn’t think so.

It’s just that it’s sounds vacuous. No disagreement — but there’s nothing practical we could do with that.

The problem is we’re missing the point. We have to stop thinking of virtues just as generic goodness.

So what exactly are virtues? Each virtue is a specific kind of habit, that anyone can acquire. Each one literally gives us superpowers. They are superpower habits, which is why I call them “superhabits.”

Let me show you why they are superpower habits. We have extensive scientific evidence from the fields of psychology and organizational behavior, over the last three decades, that each one of these superhabits makes us happier, healthier, and more effective.

Let me give you some examples. Gratitude is a superhabit. There are lots of studies on gratitude. In one study, they took two groups, one group kept a daily gratitude journal for 60 days — good way for building a habit of gratitude, it turns out — and the other group did not. At the end of the 60 days, the gratitude journal group were happier, and also had a reduction in anxiety and depression, and a reduction in chronic physical pain, compared to the control group.

Collectively, the research shows that growing in the habit of Gratitude:

makes you more effective at being grateful

makes it easier to be grateful

makes you happier and healthier

But it’s not just Gratitude. Restraint is another superhabit. Extensive research shows that having the habit of Restraint:

makes you more effective at restraining yourself; you do it more reliably

makes it easier to restrain yourself — because when something is a habit, it’s easier to restrain yourself

makes you happier and healthier

Humility is a superhabit. Again, research shows that growing in the habit of humility:

makes you more humble

make it easier to be humble

makes you happier and healthier

Are you seeing the pattern here? It goes on and on.

Okay, you might say: so grateful, restrained, humble people have easier, happier and healthier lives. How does that help me, if I tend to be ungrateful, or impulsive, or a bit arrogant? That’s just the way I am.

And this is where you are very wrong! Virtues are HABITS, that anyone can develop. If you think you are disorganized, it’s just that you haven’t yet cultivated the habit of orderliness — and you can; anyone can. If you think you are not creative, you just haven’t cultivated the habit of creativity — and you can; anyone can. If you think that you’re overly cautious, you’re ruled by your fears, then you just haven’t cultivated the habit of courage yet — and you can; anyone can.

How do you go about becoming more orderly, more creative, more courageous — or more grateful, or more restrained, or more humble? Something really helpful here is the popularization of the idea of habits in the past 10 years, through books like the Power of Habit and Atomic Habits.

These are really good books. They show you how making tiny changes, every day, can have a really big impact on your life, by creating habits.

What these books don’t tell us is which habits to focus on. But that’s ok, because we know that — the superhabits are the highest leverage habits, and so we focus on them — and we can use the methods in these books about how to cultivate habits to grow in any virtue .

What these books teach us is that taking simple, tiny steps, like saying thank you, keeping a gratitude journal, will help you grow in gratitude. Humility is an occupational hazard for leaders, like most of us in the room. Here’s an easy first step: every time you’re about to make an important decision, make a list of everything you don’t know about the decision. This exercise will help you grow in the habit of humility.

Part of what’s going on here is what is called neuroplasticity. It is the rewiring of your brain, through small and repeated changes, that makes it easier and more likely that you’ll do the thing in the future. We can also call it character development: it’s what every civilization before us did, and what we’ve largely abandoned, and the terrible consequences of this are all around us. The human person needs this kind of formation, formation in superhabits, in virtues, through repeated practice. And the beauty of it is, as you rewire your brain, it really does just get easier: easier to be effective, and easier to be good.

Now it’s not just a case of “okay, I’m gonna get me some superhabits, and my life will be better.” It’s certainly that, but it’s even bigger than that! Whatever is bothering you, whatever is the biggest struggle in your life, there’s a virtue for that, that will make that part of your life so much easier, and better. Whether it’s issues with anxiety, with relationships, with decision-making, or whatever, there is a virtue that will improve that part of your life, significantly.

How can I say that, that there’s a virtue for every part of life? The answer is in the genius of Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas shows that there are different virtues for all the different dimensions in life. He has a complete system.

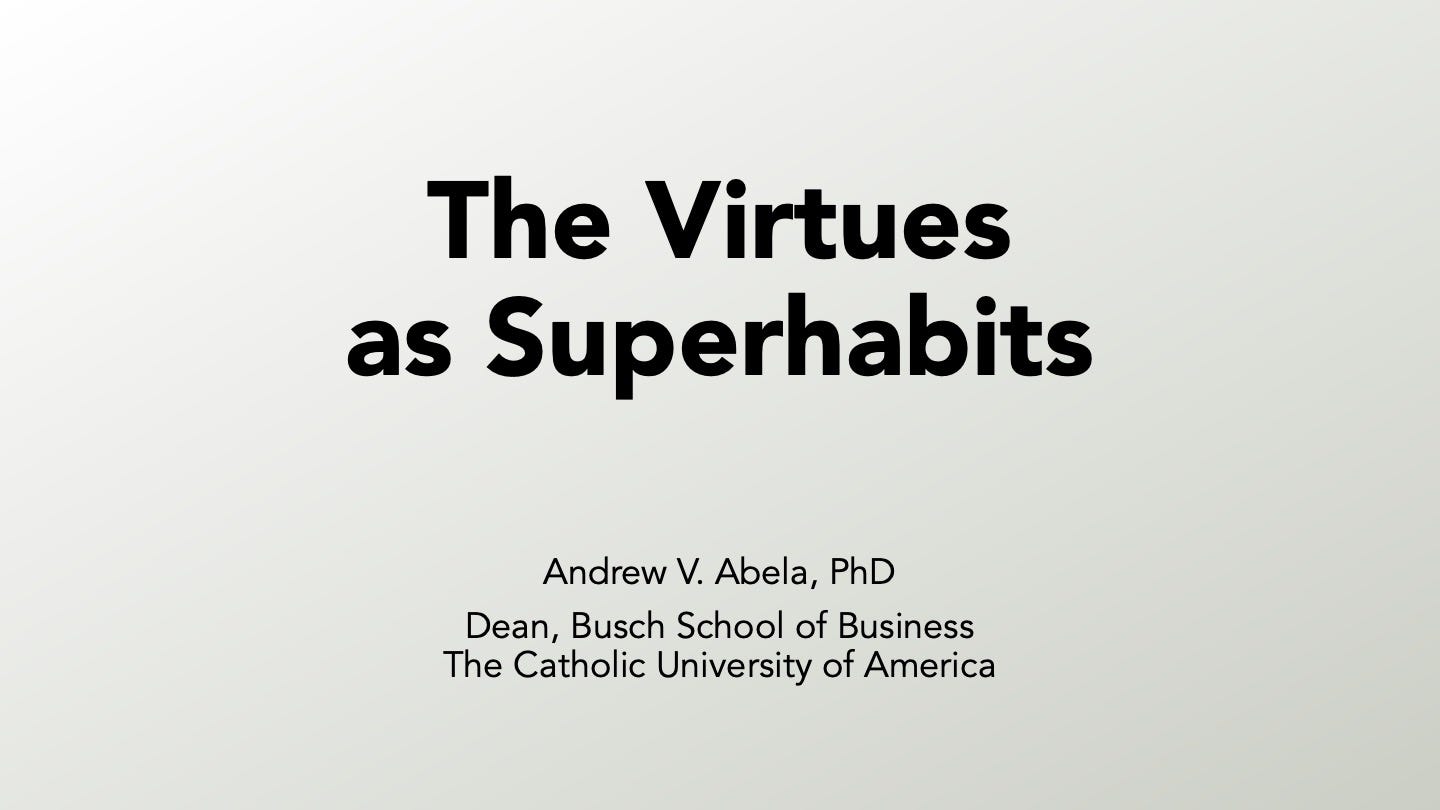

Remember those missing habits of thought, action, and feeling, that I mentioned earlier? They are a central part of his system. His system includes theological virtues, intellectual virtues, and practical virtues, the virtues for everyday life. The habits of thought, action, and feeling are the virtues of everyday life, and that’s what I want to focus on here today

The habits of thought, action, and feeling are the virtues of everyday life

So which virtues are they? Aquinas observes that thoughts, actions, feelings pretty much cover every aspect of our daily lives. Think about it — all day long, everything that occupies you, can be described as thoughts, actions, or feelings.

(Of course there are the theological virtues and the intellectual virtues too, that may be operating at the same time, but I’m just focusing on the practical side of things here.)

Aquinas then divides feelings into two types of feelings, feelings that push us away from things or situations (fears), and feelings that attract us (desires).

Here’s where it gets really interesting. You’ve heard of the four cardinal virtues: prudence, justice, fortitude, temperance? Ever wonder what’s so special about these four?

Here’s why - Aquinas explains that prudence, or practical wisdom, is the habit of making wise decisions and is for managing our thoughts. Justice is the habit of being fair to others and respecting their dignity, and it manages our actions. Fortitude, or courage, is the habit of moving forward despite your fears, and Temperance, or Self-discipline, is the habit of only following your desires when it makes sense to do so.

So there’s a cardinal virtue for managing our thoughts, actions, and both kinds of feelings — every aspect of our daily lives.

This is intellectually very satisfying, but if Aquinas stopped here, it wouldn’t actually be that helpful. Because each of these cardinal virtues is no small thing to develop. If you’re struggling with unwanted desires, for example, and I told you that you just need to get better at Self-discipline, that wouldn’t be very helpful.

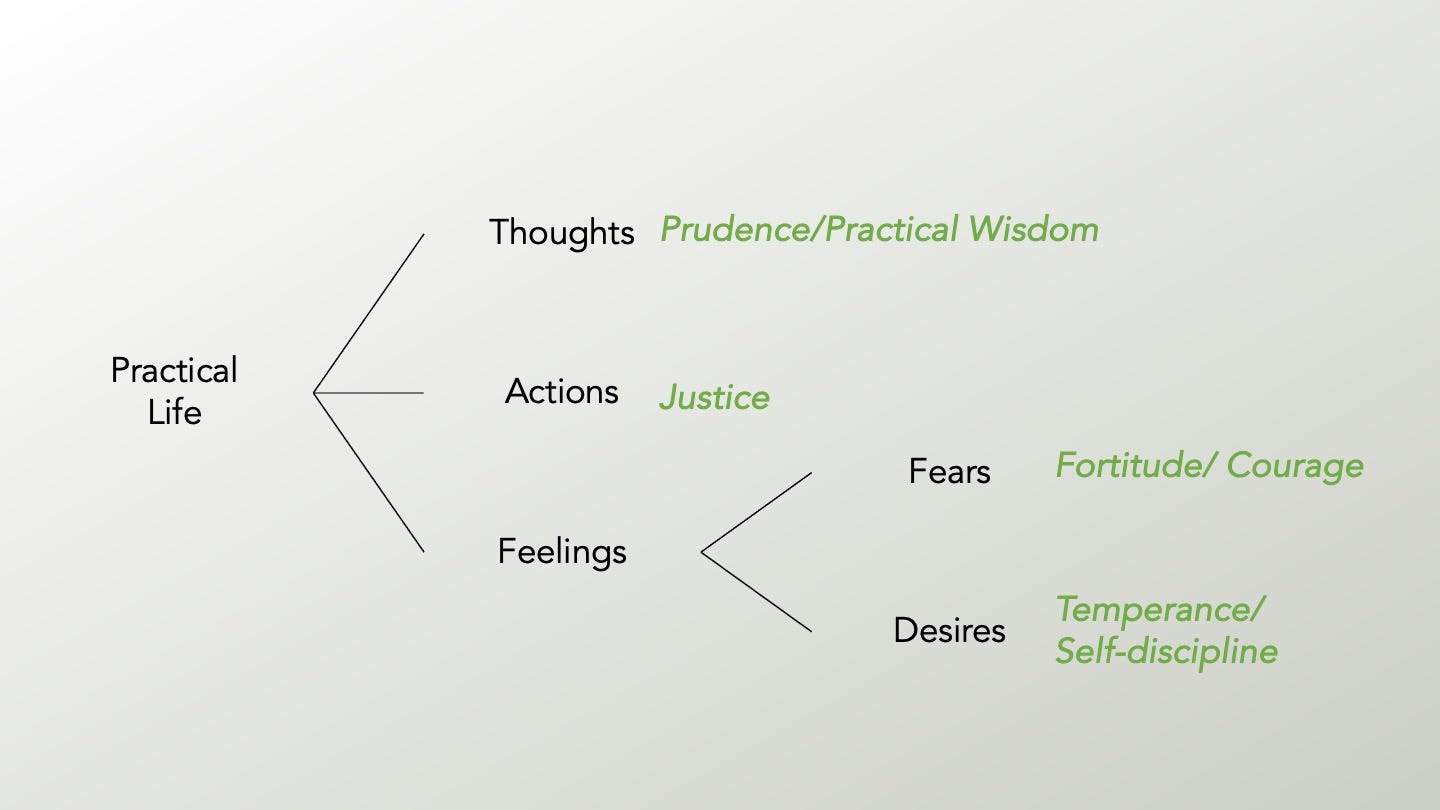

Here’s where Aquinas’ genius really kicks in. He observes that each of the four cardinal virtues has several other, smaller, virtues that are allied to it, which are easier to develop, than, say Self-discipline itself. That’s why they’re called “cardinal.” The Latin word cardo means hinge, or pivot: numerous other virtues pivot around the cardinal virtues. If you work on one of these smaller virtues first, that’s much more manageable.

For example, Courage has four allied virtues, one for each of four different types of challenge. Aquinas divides challenges into ones you can overcome, and ones that you have to endure, at least in the short term. For example, if you’re suffering from a chronic disease, you will certainly try to get better, but in the meantime you have to endure it.

So what are the relevant virtues for the different types of challenges? For challenges that have to be overcome — Aquinas is very practical here — he says there are fundamentally two ways to overcome a big challenge: with, and without, spending large amounts of cash. You can solve a big problem by putting in lots of effort, that’s the virtue of Magnanimity, from the Latin magna anima, “big souledness,” the habit of tackling large problems with enthusiasm. You can also solve big problems by spending lots of money, and that’s the superhabit of Munificence.

These are two virtues in plentiful supply in this room. Magnanimity is the virtue of entrepreneurs, leaders, builders. Munificence is the virtue of great philanthropists — the habit of being willing to spend large sums of money to solve an important problem. (It has to be large sums of your own money; there’s no virtue for spending lots of other people’s money).

Challenges that must be endured are divided into physical and mental challenges. For physical challenges, like tiredness, or sickness, there’s Perseverance, the habit of continuing to move forward even when you’re tired, worn out. For mental challenges, like anxiety and depression, there’s Resilience. It’s the habit of taking action even though you’re anxious or depressed, which, paradoxically, then makes you less anxious or depressed. So if someone wants to get better at dealing with anxiety, or depression, they should grow in the superhabit of Resilience, by practicing small steps, every day, reframing thoughts and taking little steps forward.

Incidentally, another name for developing the virtue of Resilience is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, which is the most successful treatments for anxiety and depression today — and Aquinas anticipated it by 750 years.

See how all this helps. If you’re trying to grow in Courage, you don’t start with Courage itself. You start with, say, Perseverance, practicing a little bit every day, to keep going beyond the point when you would normally give up because you’re tired — maybe just 10 minutes longer. Over time that becomes easier, you get better at Perseverance, and that in turn helps you to grow in Courage.

Maybe it’s not clear yet. Let me give you one more example, Self-discipline. This can be a tough one, because where Courage has four allied virtues, Self-discipline has 15. Self-discipline is the superhabit for dealing with desire, the habit of only following your desires when they make sense.

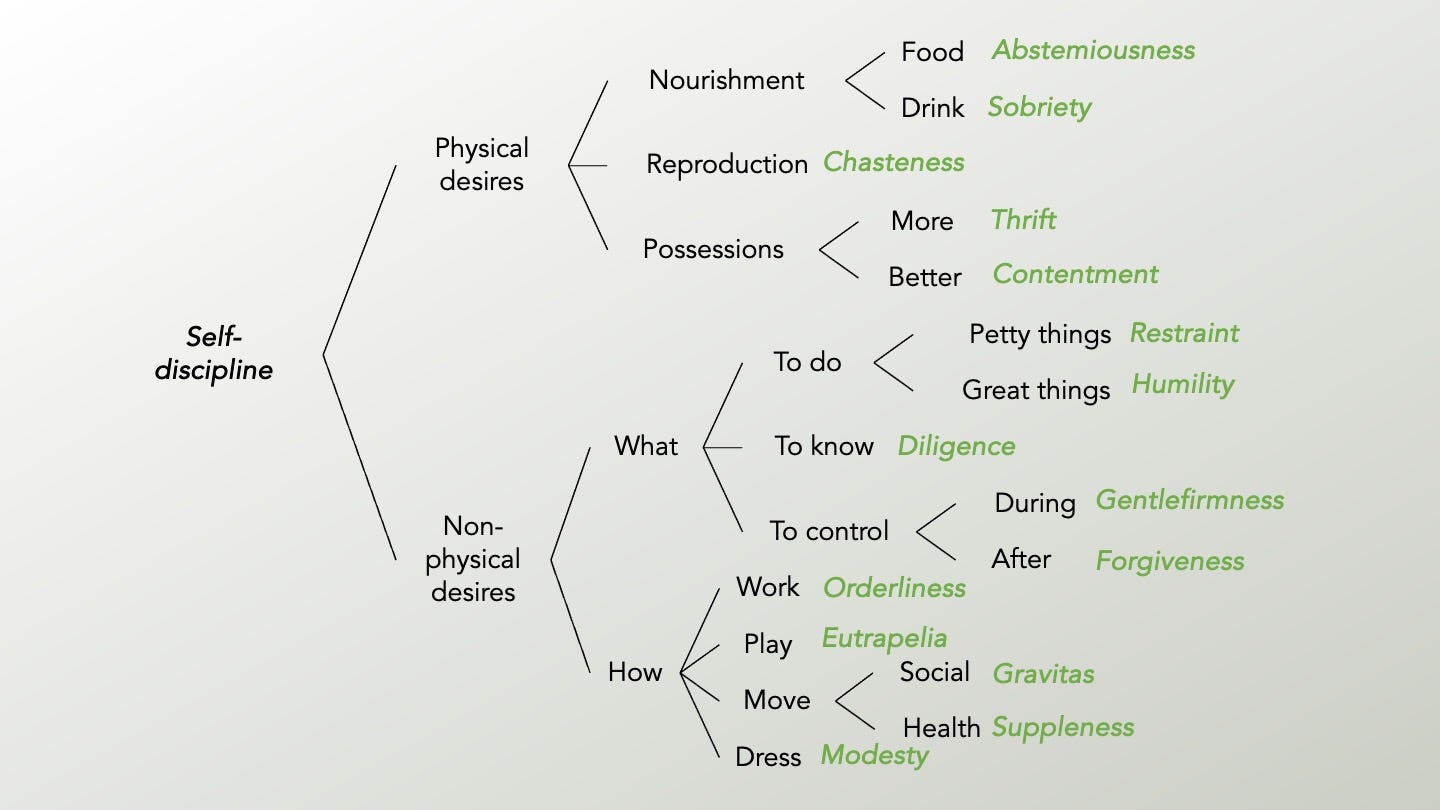

Aquinas identifies 15 types of desire, and presents a different virtue for each. Here they are:

Do you see, now, why it can be tough to grow in Self-discipline directly? If you try to grow in self-discipline itself, you’re effectively trying to grow in 15 virtues at once! Instead, pick the 1 desire that makes your life most difficult right now, and just work on that. Perhaps you struggle with the desire to do impulsive things. In which case you should focus on the virtue of Restraint for a while.

I hope you are starting to see how the implications of all this can be simply enormous. How small changes, repeated, can help anyone grow in any virtue, and how this can be a source of tremendous improvement, in our own lives, in our families, in our schools, in our organizations, and in our companies: how so many of the problems facing our society today could be improved significantly if we could get more people to grow in virtue. By taking tiny little steps in the right direction.

If you’re wondering: if this stuff is so powerful, and yet so practical, how come we haven’t heard about this before? Well, you have. The problem is you usually hear about virtue from philosophers. And philosophers tend to be, well, philosophical.

I’m not a philosopher. I’m a business dean. I see the immense practicality here, how useful it can be, for all the problems we’re facing. And I’m not just a business dean, I’m a professor of marketing — so I’m here to promote virtue, as a solution to so many of our problems!

There is so much more to say, and so little time, so here are some ways for you to learn more:

You can subscribe to this Substack.

You can pre-order my forthcoming book, Superhabits: The Universal System for a Successful Life, from the publisher or from Amazon.com.

Finally, here’s a video showing how each of the cardinal virtues and their allied virtues come together to form the Anatomy of Virtue, according to Aquinas’s system. Watch this, and then download the Anatomy here.

Superhabits, virtues, are superpowers that anyone can acquire, that make life easier, happier, healthier, and more effective. Our country needs them desperately. Let’s go do this!

Callum Borchers, ‘The Workers Who Do Everything on Their Phones—Except Answer Calls’ Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/lifestyle/careers/hybrid-workers-phone-calls-telephonophobia-8697a451?reflink=integratedwebview_share